The archives of nineteenth-century surgeons are full of material that makes for sad or unpleasant reading, but this story, while it certainly contains more than its fair share of tragedy and suffering, is a nautical tale so remarkable it might have been plucked straight from the pages of a Patrick O’Brien novel.

It is contained in a letter sent to the leading London surgeon Sir Astley Cooper (1768-1841) in September 1824 and now held among his personal papers in the archives of the Royal College of Surgeons. Its author was John Lennon (1768-1846), a merchant navy officer from Downpatrick in Ireland, then resident in Rotherhithe, London. To say that Lennon led an adventurous life would be an understatement. He first served as a midshipman during the American War of Independence and, in a career which included service in the French wars (1793-1815) and the American War of 1812, he was captured, capsized and involved in any number of engagements with the enemy.

Lennon’s letter to Cooper relates the extraordinary case of a ‘musquet [sic] ball I received in my body on the morning of the 25th of Dec 1797’. A month before this incident he had taken command of Favourite, a ‘Private Schooner of war’ based out of the occupied French island of Martinique. In this period it was a common practice in time of war for merchant vessels to receive what were called ‘letters of marque’, which gave their captains permission to attack enemy shipping, the incentive being that they got to keep a percentage of whatever ‘prizes’ they captured. In the previous year, the Kingdom of Spain had made an alliance with the nascent French Republic and declared war on Britain. Lennon therefore took Favourite out of port to raid the Spanish Main. After ten days at sea he put in to Kingston, Jamaica, with ‘one French and two Spanish Prizes’ and, after refitting, sailed out again for Spanish waters on 17th December.

On Christmas Day 1797, Lennon and the crew of the Favourite were cruising off Cartagena de Indias in modern-day Columbia. At 5am they spotted a sail to the West-South-West and at 7am ‘came up with the chase and found her superior in force to ourselves’. Having prevented this vessel, which was sailing under a French flag, from reaching safety ‘under the guns’ of Cartegana’s ‘Fort Bocca Chicco’ (the Fort of San Fernando de Bocachica), Lennon engaged her. Unfortunately, however, this coincided with a falling off of the wind and Favourite found herself becalmed. Lennon perceived two ‘well manned and armed’ Spanish vessels being rowed out to assist his opponent. Unable to manoeuvre and having no choice but to fight or surrender, Favourite was engaged by the three vessels for over an hour and twenty minutes. Caught in a triangle of fire, her crew suffered terribly. All the officers were killed or wounded, ‘as well as several of the crew’.

In helping the ‘remaining few to their quarters’, Lennon was hit by a musket ball which entered ‘between two of my ribs close to the backbone on the right side’. He fell face down, but soon leapt to his feet to find ‘blood [coming] from my mouth very fully so that I lost all use of speech’. Feeling faint and ‘with a great heat from the wound in my back’, he fell upon the Quarter deck where he remained until his ship was boarded by the enemy. Having failed to strike their colours (the conventional sign of surrender at sea), his wounded crew were mostly put to the sword. Lennon would have suffered the same fate had an officer, who saw that he could not resist and suspected he was the commander, not ‘rescued [him] from a blow made at [him] by a Sabre’.

Lennon was subsequently moved from the Quarter deck, though many times he feared he would choke to death on the blood congealing in his throat. He attributed his survival to the commanding officer of the French vessel, who showed great ‘humanity’ to him. Locating the wound, his captors bandaged him up tightly, which gave him great relief in stopping the ‘circulation of air from the wound’ (it later turned out that he had been shot through the lung). Taking Madeira wine and water (the former a common medicament in this period, especially for Brunonians, who thought of it as a stimulant), Lennon experienced a ‘warmth’ in his stomach which he considered to be ‘the means of my bringing up considerable lumps of congealed Blood more freely than before’.

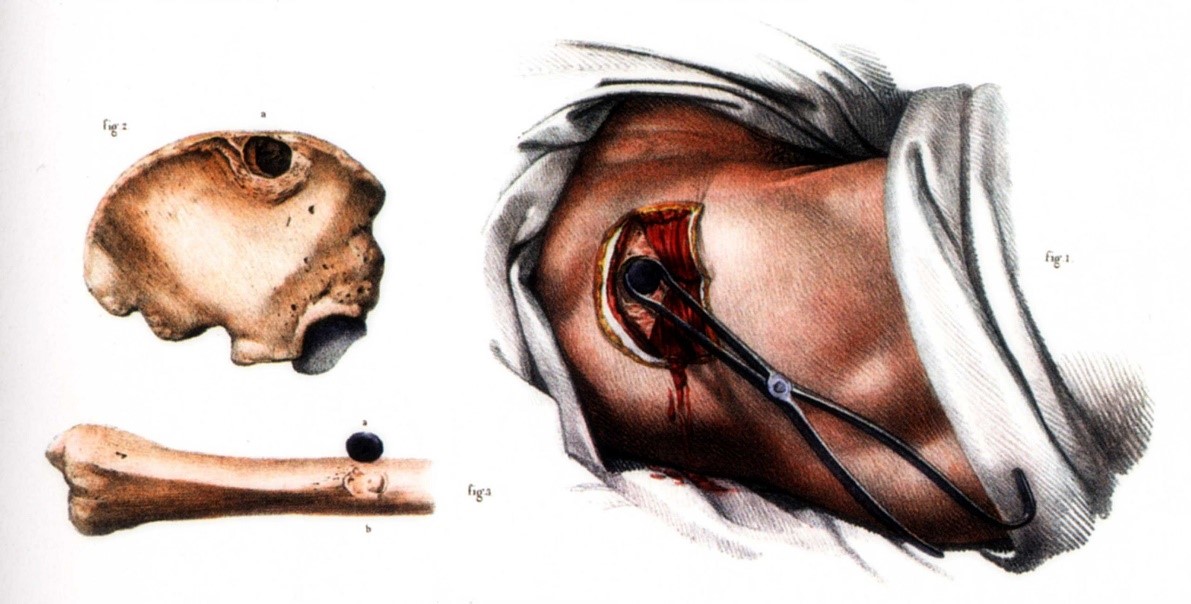

Later that evening, Lennon and the remnants of his crew were taken ashore to the Hospital in Cartagena. The surgeons initially attempted to extract the ball but to ‘no effect’. ‘During this operation’, he wrote:

I was told I swooned away, and remained so for several hours, and had not I shown symptoms of life when I did, its [sic] very likely I should have been taken to the Dead house with several of my poor fellows that died of their wounds during the night.

Lennon remained in hospital for five weeks, attended for much of that time by a constant fever and unable to rest adequately, for the pain caused by the movement of the ball within him. Eventually, however, the wound began to ‘fill up’. At about this time, a Spanish frigate was due to sail from Cartagena to Havana (on modern-day Cuba) and Lennon successfully petitioned the Governor to allow him, together with his crew, to take passage on her, in hope that they might be exchanged for Spanish prisoners.

Lennon’s request was granted and he set sail for Havana on the Spanish frigate, receiving during his voyage, as he wrote, ‘great attention not only from Surgeon but the Captain, Officers and Passengers’. Unfortunately, however, although he arrived safely in Havana, he found himself in prison where his wound ‘not being properly attended to … broke out again with very great discharge’ which weakened him very greatly. He was once more admitted to hospital where the surgeons ‘very much wished to have my consent to operate so as to Extract the Ball which I would not agree to’. Eventually Lennon recovered, and was returned to prison. There he remained for about four months when one day, ‘to our great joy’, he and his crew were exchanged for some Spanish prisoners sent on a cartel from Bermuda.

What is notable about Lennon’s treatment during his time in captivity is the care and attention his wounds received from the French and Spanish surgeons that he encountered and the general compassion exhibited towards him by his captors. Needless to say, as the commander of a privateer he was a valuable commodity, one whose value was eventually redeemed in exchange for Spanish prisoners. But it is nonetheless remarkable that a man who was one sword stroke away from being killed while unconscious should then be subject to such continual and considerate care. The ‘ethics’ of war then, as now, are a peculiar phenomenon.

After his release, Lennon made his way back to London where he consulted with the surgeon William Blizard (1743-1835) and ‘other Gentlemen of the Profession’ who recommended that no attempt be made to extract the musket ball from his body and that he might live ‘as long with it as without it’. After eight months the wound was fully healed and Lennon headed back to the Caribbean.

On 17th March 1798 he was in Kingston when he was invited by some fellow Irishmen to celebrate St Patrick’s Day. During the gathering he was taken with a fit of coughing ‘which continued for some time’ until, at length, he brought up ‘something of substance into my mouth’. On examining this substance he found, to his ‘very great surprize’, that it consisted of ‘the piece of my shirt and Jacket that the Ball had forced into my Body, the shirt being Linen and the jacket nankeen, both the pieces being attached to each other’. After expelling these items, Lennon experienced great relief in his breathing, and he supposed that the cloth had been forced into his lungs where it had remained for ‘fourteen months and twenty-three days’.

Lennon never did bring up the ball. After three years it settled into a ‘resting place in the right front of my body by the lower edge of my ribs’. Even 27 years later, as he wrote his letter to Cooper, he was unable to lie for more than 20 minutes in any position other than on his right side without great discomfort and if he were to stumble while walking, the jarring of the ball would cause him agony. Lennon carried a physical reminder of that fateful day within him, through all his subsequent adventures, until the day he died, aged 78.

For Astley Cooper, on the other hand, this remarkable tale had deep surgical significance. Surgeons in this period, even civilian ones like Cooper, were fascinated by wounds, especially those of war, and would examine or read about them whenever possible; and in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, during 20 years of war, there were no shortage of such stories to go round. There had been a good deal of debate within surgery for some time as to whether it was prudent to remove a musket ball or let it keep in. As Lennon’s experience reveals, Spanish surgeons were apt to attempt extraction. By this time, however, the growing consensus in Britain was to avoid the risks of extraction if at all possible. As John Abernethy (1764-1831) told his students in 1819:

Now this notion of looking after a ball is a very natural one and we are constantly reading in novels (which however I would not recommend you to read) that “Sir Harry received a Ball but then it was extracted and Sir Harry was doing well” – but it is very bad practice.

For surgeons such as Astley Cooper then, Lennon’s tale served as a remarkable example of the human body’s capacity to both retain and expel foreign objects with little or no risk to health.

Resources

File of letters and notes on cases sent to Sir Astley Cooper, MS0008/2/2/7, 1813-1838. Royal College of Surgeons.