Principal Investigator Dr Michael Brown considers the emotional content of the famous war paintings of the surgeon Charles Bell.

I recently had an article accepted for publication by the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies which explores the relationship of the Scottish surgical siblings John Bell (1763-1820) and Charles Bell (1774-1842) to war, especially their imaginative and professional investment in military surgery and their complex emotional reactions to the experience of treating the wounded. Drawing on Yuval Noah Harari’s argument that the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw war configured as an increasingly transcendent emotional event, it considers the difficulties of translating both professional identities and emotional experiences across a widening civil-military divide.[1]

In this regard, what is particularly interesting about both John and Charles Bell is that neither man was a military surgeon. While Charles wrote in 1807 that ‘of all things I should like to be kept and sent to the armies as a surgeon’ and while John agitated for a role in the training of military surgeons, neither had served in the army or navy and neither had any direct experience of battle.[2] And yet, in their work, both men imagined themselves as battlefield surgeons, harnessing the emotional and cultural capital of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars to shape their identities as surgeons.

While John Bell’s engagement with the war wounded is not especially well known outside of specialist circles, his younger brother’s experiences are far more widely discussed. This derives, in part, from the emotionally expressive letters that he sent back to England from Brussels in the aftermath of Waterloo. Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) said that reading one of Charles’ letters to his brother George (1770-1843) ‘set me on fire’ and it served as inspiration both for his own trip to the Continent as well as his semi-fictional account of Waterloo, Paul’s Letters to his Kinsfolk (1816).[3] But even more than his letters, it is Charles’ paintings of the war wounded that have excited academic attention, and it is revealing that, outside of medical history, interest in Charles Bell has largely come from art historians such as Anthea Callan, Aris Sarafianos and, most notably of all, Philip Shaw.[4]

There is much more to be said about Charles’ experiences of the effects of war and how his emotional self-reflection fits within the wider affective cultures of what I call ‘Romantic surgery’. This aspect, which is frequently overlooked by those who view him predominantly as an artist, rather than a surgeon, is what my article seeks to do. But even in terms of his art, which has been subject to far greater critical scrutiny, there is still more to be said. In the main, scholars have been attracted to his images of the wounded of Waterloo and have emphasised his representation of pain and suffering, as well as his evocation of sublime pathos. By contrast, they have said rather less about his earlier paintings of the wounded from the Battle of Corunna (1809), men whom he encountered during his trip to Halsar Hospital in Gosport and, later, at York Hospital in Chelsea.

These paintings exhibit certain similarities to his later sketches from Brussels, particularly in their visceral quality. This is certainly true of his images of gunshot wounds to the skull, thigh and testicles (Figs 1, 2 and 3).

But, in other respects, they differ. For one thing, they are more obviously painterly, since they are finished in oils. For another, they are just as enamoured of male beauty as they are concerned with bodily disfigurement. Take, for example, his three images of chest and abdominal wounds (Figs 4, 5 and 6).

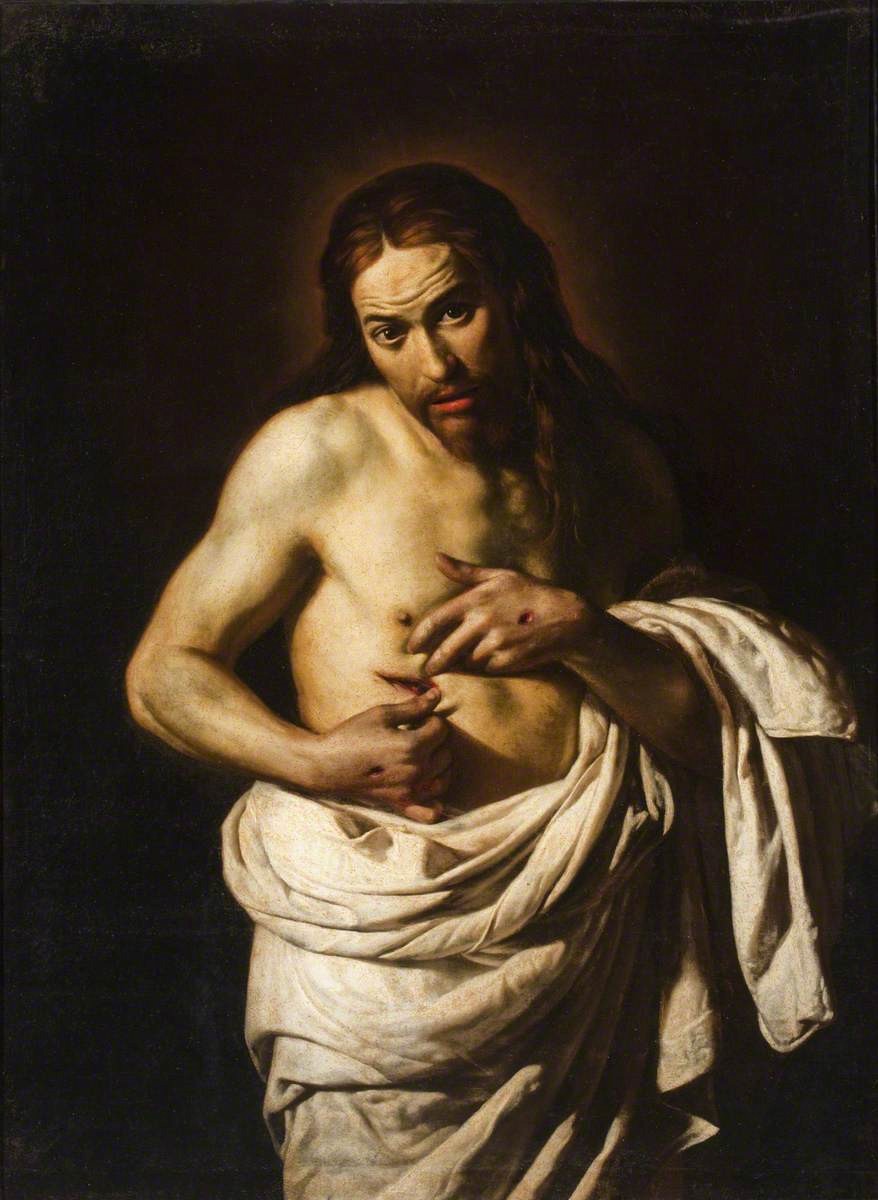

In Fig. 4, in particular, the pose, though no doubt calculated to display the wound, resonates with the poses of other male models, especially boxers, who were regular subjects of the anatomical and artistic gaze. Meanwhile, in other instances, the men’s display of their wounds evokes the traditions of Christian iconography, notably the stigmata (Fig. 7) and religious ecstasy (Fig. 8), as well as contemporary neoclassical subjects such as Jacques Louis David’s Death of Marat (1793) (Fig. 9).

That Charles should have conceived of his sitters in this way is hardly surprising. He was well schooled in art theory, having published a book on the expression of emotion in painting (1806) and competed (unsuccessfully) for the chair of Anatomy at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1807. Moreover, his interest in the male form and its representation is well documented in his letters. In 1808, for example, he wrote to George that he ‘had been grumbling for some days that comparisons of the modern athletes and the antique had been making, and exhibitions of Jackson, the boxer, etc. without my presence [sic]’. However, ‘On Saturday when I came home I found that Lord Elgin had called, and written a note requesting me to come and see an exhibition of the principal sparrers naked in his museum. I went, and was much pleased’.[5] Furthermore, when writing to his bother about the ‘his gun-shot men’, he told him how he sought to learn from the ‘best old masters’ how to convey a ‘faithful’ representation that is ‘full of character’, as opposed to the ‘modern’ style in which the individual was ‘shaded off and indistinct’.[6]

At the same time, the ambivalence of Charles’ Corunna paintings, torn as they are between beauty and horror, pride and pity, can be ascribed to Charles’s complex affective response to Haslar. As he wrote to George, concerning his experiences with the wounded, ‘I have muttered bitter curses and lamentations, have been delighted with the heroism and prowess of my countrymen, and shed tears of pity in the course of a few minutes’.[7] In this way, Charles’ paintings can be seen to exemplify a range of emotional responses that were utterly in keeping with contemporary cultural norms, namely the religious (‘bitter curses and lamentations’), the patriotic (‘heroism and prowess of my countrymen’) and the sentimental (‘tears of pity’).

Charles’ images of the Waterloo wounded share certain qualities with his earlier paintings. The faces of the men, in particular, speak to his interest in the representation of intense emotion, approaching on occasion to what Sarafianos and Shaw have identified as sublime pain. But, in other respects, they are more ragged, less obviously aestheticized and perhaps more shocking. No doubt, this owes something to the medium: watercolours after pencil sketches done at the bedside. It also owes something to the severity of the wounds themselves, which in a number of cases are particularly extreme (Figs 10 and 11). But, as with his Corunna images, they also reflect Charles’ emotional experiences in Brussels.

Much of Charles’s surgical work was with the French wounded, who had been ‘brought from the field after lying many days in the ground, many dying, many in the agony, many miserably racked with pain and spasms’.[8] While at Haslar his emotional equipoise had been tested, but in Brussels it was almost overwhelmed, as he was confronted by the ‘most shocking sights of woe’.[9] In this regard it is interesting that, where one might expect his French patients, or even those members of the King’s German Legion whom he treated, to be ‘othered’, his sketches largely preserve the names of his Waterloo subjects, whereas those of his British subjects from Corunna remain anonymous. Despite referring to the French troops as a fierce, cruel and bloodthirsty ‘race of banditti’, he was deeply moved by their ‘plaintive cries and declarations of suffering’.[10] It is almost as if he wished to preserve, in their names, a testament to the humanity of those whose suffering he witnessed and sought to relieve (Fig. 12).

Indeed, Charles’ graphic images from Waterloo might even be regarded as a kind of emotional catharsis, an expression of sensations that were so intense as to defy language. After his return to London he wrote a letter to his friend, the Whig MP Francis Horner (1778-1817); following a lengthy description of his experiences, he apologised for ‘falling into the mistake of attempting to convey to you the feelings which took possession of me, amidst the miseries of Brussels’. Acknowledging the ineffability of what he had seen, he concluded by suggesting that ‘I must show you my notebooks, for as I took my notes of cases generally by sketching the object our remarks, it may convey an excuse for the excess of sentiment’.[11]

[1] Yuval Noah Harari, The Ultimate Experience: Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture, 1450-2000 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

[2] Letters of Charles Bell (London: 1870) Charles to George Bell, 21st May 1807, p. 96.

[3] John Gibson Lockhart, Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart, vol. 3 (Edinburgh: 1837), p. 347-50. See

[4] Anthea Callen, Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018); Aris Sarafianos, ‘Wounding realities and “painful excitements”: real sympathy, the imitation of suffering and the visual arts after Burke’s sublime’, in Thomas Macsotay, Corneils van der Haven and Karel Vanhaesebrouck (eds), The Hurt(ful) Body: Performing and Beholding Pain, 1600-1800 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), 170-201; Philip Shaw, Suffering and Sentiment in Romantic Military Art (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2013). Shaw is not an art historian in the conventional sense, but his book is largely concerned with visual representation.

[5] Letters, Charles to George Bell, 26th July 1808, pp. 125-6.

[6] Ibid., Charles to George Bell, 23rd May 1809, pp. 147-8.

[7] Ibid., Charles to George Bell, 3rd February 1809, p. 139.

[8] Ibid., Charles to George Bell, 1st July 1815, p. 241.

[9] Ibid., Charles to Francis Horner, July 1815, p. 248.

[10] Ibid., Charles to George Bell, 1st July 1815, pp. 242-3.

[11] Ibid., Charles to Francis Horner, July 1815, p. 248.