On Wednesday the 12th of February we held our Valentine’s Late Open Hearts, Racing Pulses at the Royal College of Nursing in London. Almost one hundred people joined us to explore the rich feelings associated with healthcare – from compassion and romance to anxiety and fear.

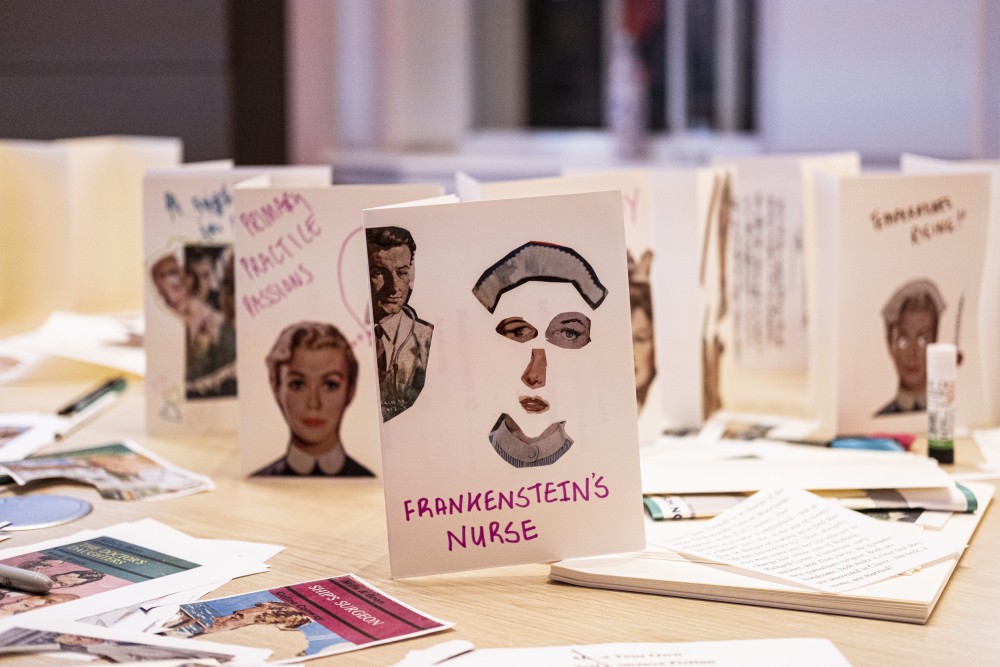

Attendees participated in a range of creative and thought-provoking activities. The Surgery & Emotion team resurrected the activity Make your own Medical Romance Fiction which we first ran at the Science Museum Late in 2018. People penned their own stories and designed their own cover art inspired by real-life ‘Doctor-Nurse’ romances published in post-war Britain. Drawing on Research and Engagement Fellow Agnes Arnold-Forster’s research, PhD Candidate Lauren Ryall-Waite was on hand to guide participants through the tropes that populate this genre and to discuss how the novels have shaped stereotypes about the surgical, medical, and nursing professions.

Clinical stereotypes were a theme that ran through many of the activities on offer. Attendees explored the various ways that feelings and their representation are central to the development and maintenance of professional identity. Indeed, a key component of clinical stereotypes is the emotional range expected or required from practitioners. The stereotypical surgeon is, for example, capable of anger, derision, and disinterest – but not care, compassion, or collegiality. He (the stereotypical surgeon is always ‘he’) also has little time for introspection, reflection, or emotional ‘self-care’. In contrast, nurses are expected to feel and expression calm, compassion, and care - regardless of the situation or circumstance.

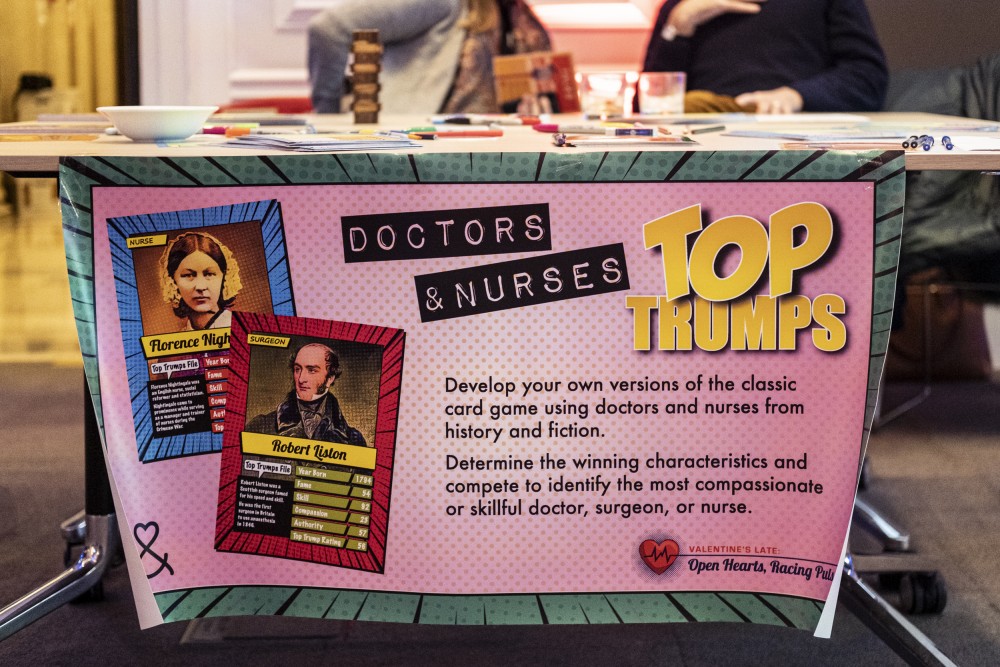

Principal Investigator Michael Brown and Senior Research Fellow James Kennaway ran Doctor & Nurse 'Top Trumps' where participants developed their own versions of the classic card game using doctors, nurses, and surgeons from history and fiction. Players determined the winning characteristics and competed to identify the most compassionate, authoritarian, or skilful healthcare professional.

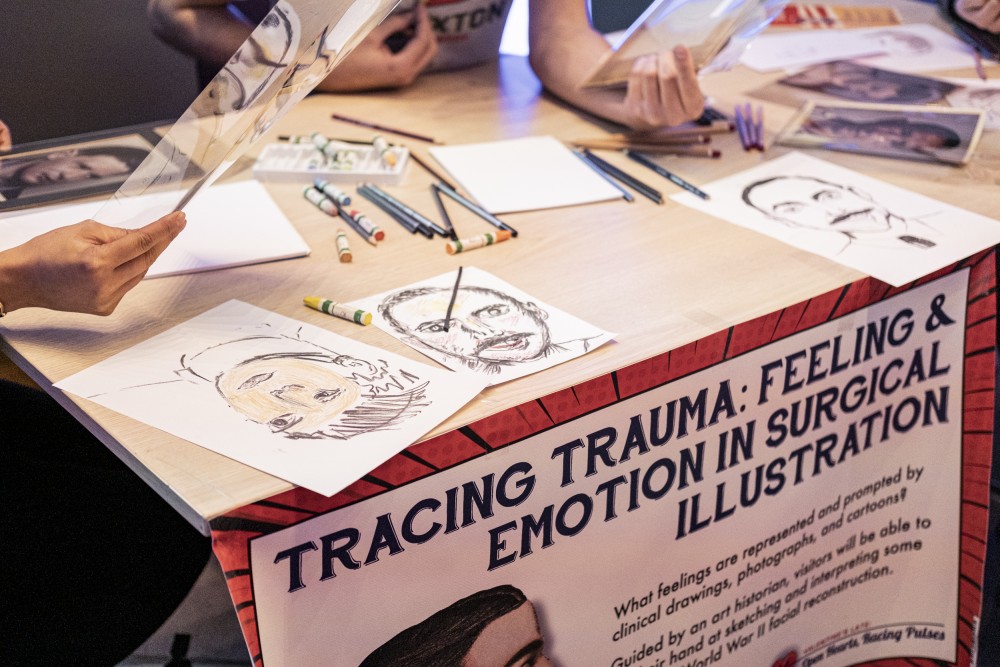

Art Historian Christine Slobogin ran a workshop on feeling and emotion in surgical illustration. Attendees had a go at sketching and interpreting some images courtesy of the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgeons, and explored the feelings represented and prompted by clinical drawings, photographs, and cartoons.

Along similar creative lines, artist, doctor, and dentist Simon Hall ran a stand called Sculptural Snogging where participants delved into the art and science of our mouths, kissing and sexual health by modelling and modifying an anatomic waxwork of their ideal luscious lips and tantalising tongues.

The team from the Body, Self, Family project at Essex University – Tracey Loughran, Kate Mahoney, and Daisy Payling – ran a pair of activities Could you be an Agony Aunt? and What do everyday health objects sound like? For the first, participants took a quiz and matched questions and answers on love, sex, and relationships from women’s magazines from the 1960s to 1980s to find out how you would fare as a twentieth-century agony aunt. In the second, attendees could listen to extract from the project’s oral history interviews out of headphones attached to everyday health objects.

Nursing research academic, Sharon Weldon, used anonymised footage of real operating theatre situations to give attendees a sense of how surgery functions and discussed communication and emotions. This activity offered participants an opportunity to look behind the scenes of surgery and see what healthcare professionals get up to while their patients are asleep (spoiler alert: doing their job and making questionable music choices).

From communication to stitching, the Royal College of Surgeons museums team and volunteers offered surgical skills training and participants tried their hands at suturing with skin pads and instruments.

Throughout the evening, attendees were attempting to solve a mystery and help nurse detective Cherry Ames discover the identity of her surgery patient. With help from Matron, they followed clues around the building seeking solutions. Successful treasure hunters were awarded with a free cocktail.

Speaking of cocktails, the magicians behind Killgrief & Comfort concocted a series of themed drinks for the evening. Tipples included the ‘RCN’, ‘Bedside Manner’, and the non-alcoholic ‘Purely Medicinal’.

The event also offered attendees an opportunity to see the RCN’s new permanent exhibition Who Cares? A History of Emotions in Nursing after hours. From birth to death and everything in between, this exhibition explores feelings in the history of nursing and contains research by Research and Engagement Fellow Agnes Arnold-Forster.

Last but certainly not least, Michael Brown, Tracey Loughran, and Sarah Chaney gave lightning talks on their historical research. Attendees learnt about everything from the history of surgery and emotion, to twentieth-century agony aunts, to sex and scandal in the nursing profession.

Attendees gave us great feedback. Plenty of people came wanting to learn more about the history of health and left satisfied. One wrote that they now have a new understanding of how ‘nurses’ private lives affected their work and how they were perceived’. Another said that they ‘learnt about the history of surgery without anaesthesia’. For some, the event prompted a desire for further study, ‘I will learn more about early women doctors – I didn’t know any of their names!’

Most of the people who came were not healthcare professionals and so many said that the event made them more appreciative of the affective dimensions of healthcare and of the emotional demands that doctors, nurses, and surgeons face. One wrote that they will ‘be more understanding about the demands that medical practitioners face’ and another said that they ‘better understand the empathy that doctors have to have’.

The premise of our project is that surgery has an under-examined emotional dimension and that stereotypes about detachment and dispassion are inaccurate. It was great, therefore, to see so many people’s assumptions challenged. One attendee wrote that ‘emotion in surgery was not something I have considered before – but this event definitely enhanced my understanding’. Another said that they will ‘see surgeons differently from before’. For another, the event made them ‘think about the role of compassion’. Someone else wrote that, ‘It made me realise that emotions are fundamental to medical practice’.

Finally, the event also changed the minds of the healthcare professionals who attended. One wrote that it, ‘got me thinking how important the role of emotions play in the life of the surgeon’ and said that in future they will be ‘more sympathetic’ towards their patients. For a participant who works in health policy, the event gave them an ‘improved appreciation and understanding of [the] range of emotions in surgery and/or healthcare’. They said that they ‘will think about the affective aspects of medicine for one of [their] current policy projects on professional identity and team-working’.