In this blog post, Lauren Ryall-Waite explores surgery and emotion in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

This blog post is taken from a paper Lauren gave at the ‘Frankenstein Unbound’ Conference in Bournemouth on 31 October 2018.

The year 2018 marks the bicentenary of the first publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Written two decades before the Anatomy Act came into force, the novel introduces the reader to Dr Frankenstein’s infamous ‘creature’. Assembled from body parts sourced from graveyards, the Creature is brought to life by the Doctor’s scientific experiments. Shelley’s novel reflects many of the issues and anxieties surrounding bodily objectification and anatomical dissection at the time immediately leading up to the 1832 Anatomy Act. (For more on body-snatching and the Anatomy Act, see the previous post from project PI Michael Brown.)

Shelley would have been aware of the practice of practical anatomy and some of the controversies surrounding the acquisition and use of bodies in surgical training. Her husband, Percy Shelley, intended on surgery as a career after his expulsion from Oxford and was known to have taken anatomy classes and to have spent time with other medical practitioners.[1] Mary was interested in the scientific practices of the day, demonstrated in the preface to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein: ‘Perhaps a corpse would be reanimated; Galvanism had given token of such things; perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth’.[2] For more on galvanism in Frankenstein, check out this article from Sharon Ruston.

Frankenstein demonstrates Shelley’s accurate knowledge of anatomical practice in the early nineteenth century. The Creature is a powerful symbol of surgical skill as well as a potential warning of scientific consequences. Victor Frankenstein is torn between crafted creator and tortured soul; possibly a romantic image of how surgeons were perceived to be.

Shelley shows her understanding of the practice of anatomical necessity through her descriptions of protagonist Victor acquiring bodies for his work: ‘a churchyard to me was merely the receptacle for bodies deprived of life…my attention was fixed upon every object the most insupportable to the delicacy of human feelings’ (52). Violating what was considered a sacred space, the anatomist was forced to go against social norms in order to practise his work.

Victor is aware that his yearning for knowledge overpowers such ‘human feelings'. So too it must have seemed to the wider public that surgeons, in their practice of anatomy, had turned off their emotions to what would be regarded as decent, or ‘normal’, behaviour. Anatomical spaces and preparation rooms were considered to be dirty, stinking spaces, where surgeons in training took recreational drugs such as cannabis to offset and detract from the smell of decay.[1] Rowlandson depicts such a space in what is believed to be Hunter’s dissecting room in the image below.

Lynda Payne quotes a student of Hunter who was residing within the anatomy school, politely referring to his bedroom as ‘not the most pleasant in the world’, being next to the dissecting room containing the corpses and near Hunter’s preparation space.[1] It is evident why the practice of anatomy had a reputation for being dirty, and how it came to be feared by the public.

Fear was inherent in the legal practice of anatomy before the 1832 Anatomy Act. The Murder Act of 1751 stated that under no circumstances could the body of a murderer be buried.[2] By sentencing a criminal to be executed for their crimes, death was only the penultimate punishment; dissection and dismemberment was the final penance.

Historian Jonathan Sawday suggests that the Murder Act was

designed specifically to evoke horror at the violation of the body and denial of burial to the offender. The denial of burial, in particular, was intended to evoke an added dimension to capital punishment, in that it drew upon widespread belief that lack of proper burial … involved the posthumous punishment of the criminal’s soul which would not rest.[3]

The acquisition of executed criminals by surgeons was intended to deter people from serious crimes, but accepting these corpses forced anatomists to play a part in punishing criminals. The criminal aspect of the executed corpse inherently linked being anatomised with being a wrongdoer, of receiving a punishment which followed into the afterlife – insofar as one believed in bodily restoration after death.

In Frankenstein, the Creature, made from body parts sourced from graves, commits multiple murders – an offence which would invoke capital punishment. Shelley may well have been actively linking anatomised remains with criminality; even bodies which were not taken from the gallows could be linked to wrongdoing due to the years-old association between villainy and being dissected. Victor’s description of his enthusiasm being checked by his anxiety may well have been an accurate emotional account of surgeons who had little choice but to participate in doling out such eternal punishment if they wished to continue to study their craft (59).

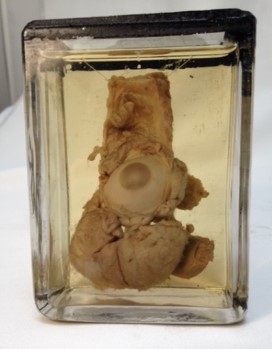

The Creature is physically an anatomical specimen; made from assembled parts, he comprises individuals chosen for their physical attributes in the same way surgeons chose individual body parts to preserve as specimens. His encounters with people lead to him being received with scorn and horror due to his terrifying appearance. Victor Frankenstein had the power to make a dead thing – or many dead things – come to something resembling life. However, it is clear that the ‘life' Dr Frankenstein creates is not quite equal with the vitality that comes naturally. Victor describes his first encounter with the Monster once it is animated, pointing out his beauty until he reaches the exception: ‘these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set’ (59). This description of watery eyes corresponds closely with the eerie anatomical eye specimens which float in preserving fluid in medical museums; the iris colours are dulled and tinged with grey, creating a stark difference in appearance to those of living people.[4]

The practice of anatomy, while grisly and often ethically challenging, was an essential aspect of being a humane surgeon at this time. It required difficult, and occasionally criminal, action in order to achieve its aims. In Frankenstein, the Monster brings together the difficulties and the fears associated with anatomical dissection, tormenting the protagonist. If we use Frankenstein to explore the wider social understanding of surgical practice in this period, Victor’s torment may be a realistic reflection of the difficulty surgeons faced in their attempts to improve their practice. When the scientific is pitted against something considered as sacrosanct as the human body, it is inevitable that it will have an emotional cost for all parties involved.

[1] Sharon Ruston et al. 'Vegetarianism and Vitality in the Work of Thomas Forster, William Lawrence and P. B. Shelley’, Keats-Shelley Journal, 54 (2005): 113–132 (p. 115).

[2] Alan Rauch, 'The Monstrous Body of Knowledge in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein’, Studies in Romanticism, 34.2 (1995): 227–253. For a wider discussion surrounding the added introduction in 1831 see also: James O'Rourke, ‘The 1831 Introduction and Revisions to Frankenstein: Mary Shelley Dictates Her Legacy’, Studies in Romanticism, 38.3 (1999): 365–385. Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (London: Penguin, 1818), p. 38.

[3] Elizabeth T. Hurren, Dying for Victorian Medicine: English Anatomy and Its Trade in the Dead Poor, c. 1834–1929 (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 85.

[4] Quoted in Lynda Payne, With Words and Knives: Learning Medical Dispassion in Early Modern England (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2007), p. 104.

[5] Ruth Richardson, Death, Dissection and the Destitute (London: Penguin, 1988), pp. 5-36.

[6] Jonathan Sawday, The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), p. 55, quoted in: Jane Hubert and Cressida Fforde, 'The Reburial Issue in the Twenty-First Century', in Heritage, Museums and Galleries, ed. by Gerard Corsane (London: Routledge, 2004), pp. 107-121.See also Richardson.

[7] See Royal College Surgeons Edinburgh museum catalogue number GC. 2565, for example of a dissected eye with a watery appearance.