PhD Candidate Lauren Ryall-Waite explores the Hey family collections at the University of Leeds Special Collections.

Earlier this year, I visited the University of Leeds Special Collections, housed in the fantastic Brotherton Library, on the search for some personal experiences of nineteenth-century dissection. To my delight, the Hey family collections contained some insightful personal commentary on the practice and learning of surgical dissection through the eyes of a trainee surgeon in the early nineteenth century.

In 1831 Samuel Hey had arrived in Leeds, ready to begin his new career as a surgeon. Samuel was born into a surgical family and began working at the Leeds General Infirmary under the supervision of his Uncle William Hey when he was just sixteen.[1] Samuel was also one of the first students at the new Leeds Medical School, keeping his older brother, William Hey III, informed of his education with a series of letters detailing his experiences. Leeds had grown into a large industrial city by the first part of the nineteenth century, giving medics plenty of opportunities to encounter factory floor injuries and poverty-related illnesses.

The letters detail Samuel’s first encounter with an operation, ‘I went to the Infirmary the morning after I got here and the first thing I saw was an operation of a man who had received a compound fracture of the leg…I was not sick, tho’ it made me feel rather squeamish.’ [2] Not vomiting while witnessing a gory operation is a success he wanted to share with his older brother. Samuel continues to describe how the sores are worse for beginners to bear than the operations, adding a small boast that the sores do not bother him in this way and that dressing gives him an appetite.

Sores such as these were laced with foul-smelling pus and blood. It is unsurprising that these were some of the more difficult afflictions to treat for trainee surgeons.

As the letters continue, Samuel details the harvest of limbs he witnesses being amputated, describing a 'plentiful crop of arms' being cut off in his letter on 15th September, but only one leg. He also exposes a vulnerability to his brother,

‘I am sometimes afraid of the dying…I rather expect a post mortem examination tomorrow, which I understand is the most horrible thing possible, on account of the intolerable stench, which is so bad that you cannot wear the coat that you have on at the time, again, except for the same purpose. ’[3]

I wonder whether this is an opportunity to share something with his brother he perhaps could not share with his fellow surgeons. Having several eminent surgeons in the family probably put pressure on Samuel to perform well while training in Leeds, and there would likely be an expectation he would do well as his family had previously. In sharing his fear of the dying, Samuel might indicate a vulnerability not often discussed with fellow medics.

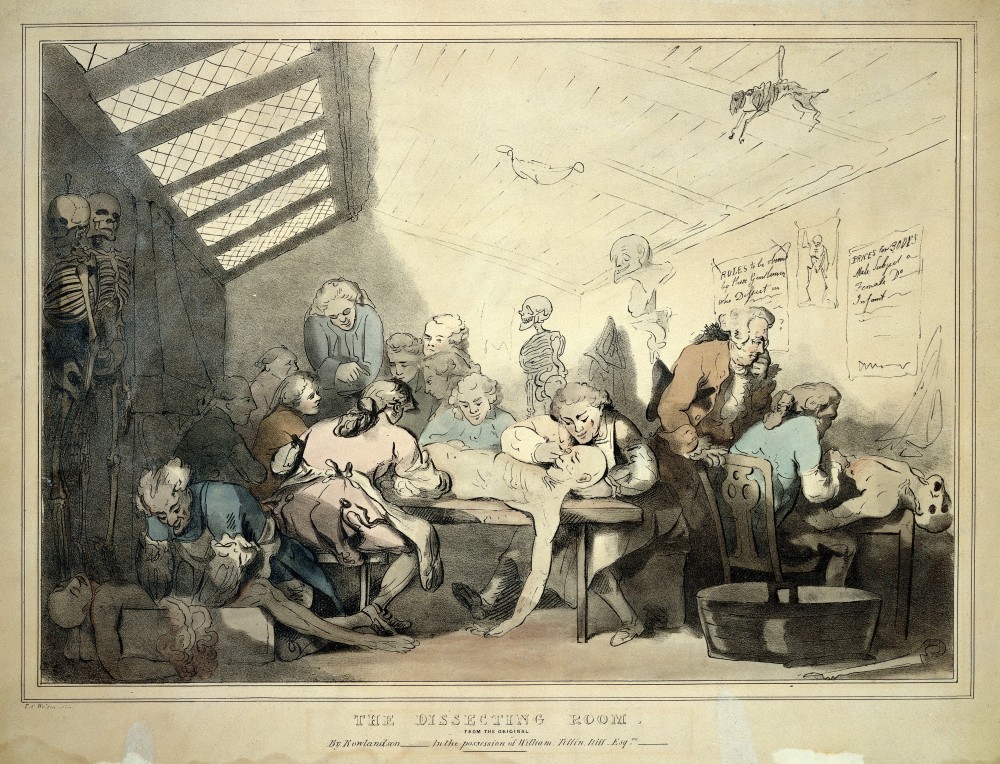

Through tracing Samuel’s correspondence, it is possible to spot where he either lost or masked this trepidation in the face of the dying and post mortems, and it happens remarkably quickly. On 8th February 1832, Samuel describes his regular dissecting practise to his brother, ‘I contrive to dissect for about three hours every morning…I got a lower extremity, I gave a guinea for it.’[4] Dissection at this time was considered essential for surgeons in both familiarising oneself with the human body and in preparing for operating on living patients. In 1800, acclaimed surgeon James Parkinson wrote in his essay ‘The Hospital Pupil’, a publication designed to promote the study of medicine and surgery, that ‘All the sciences, a knowledge of which you are now about to obtain, bear closely…but anatomy is the keystone, with which they must be held together…Anatomy then must be your first and chief object.’

Samuel’s letter goes on to acknowledge how hard dissecting is for new students, and expresses his newfound enthusiasm for the subject;

‘Dissecting is beastly work to a fellow who is new to it, I like it very well indeed now. I could cut my dinner in the dissecting room with the greatest ease; indeed, I often wish for it, it gives one such a good appetite.’ [5]

In a relatively short time, Samuel Hey had gone from admitting a fear of the dying and displeasure at having to strip down a body, to expressing his desire to dissect cadavers where he eats his dinner. Samuel may be acting the braggart here in writing to his brother or wanting to make up for the admission of fear he had shared previously. I consider that this change in tone towards working with corpses was a result of him declaring himself to now be a surgeon, using a bold statement to announce his acceptance in this role. He was not just acting as a surgeon, but thinking and feeling as one also; who else but a surgeon would wish to dissect a cadaver on their dining table?

If we consider the importance of practical dissection to surgery at this time, it is clear that it was necessary to dissect. Dissection required overcoming feelings such as disgust and fear, performing dissections on rapidly decaying bodies in rooms which were poorly lit and badly ventilated. Samuel goes beyond overcoming his fear and into the enjoyment of practical anatomy. The claim about eating his dinner while he dissects might have been posturing for his brother, but in writing this, he was also demonstrating he was in a space where his peers would not judge him for wishing a corpse alongside him while he carved it up along with his dinner.

For my research into the emotions of surgeons undertaking dissection, these exchanges help to humanise a practice which has been associated with questionable ethical practice throughout history. The acquisition of corpses in the early nineteenth century required working with body-snatchers and the willingness of surgeons to turn a blind eye to how bodies came to be on the dissecting table. While surgeons did not always want to be a part of the morally questionable acquisition of corpses, it was a reality that they had to operate within. I imagine dark humour and a pragmatic approach assisted them in performing their work under such conditions.

Joking about dining while he dissects indicates that Samuel had taken up the mindset and emotional attitude of the early nineteenth-century surgeon after just a few months of training. Non-medics of the time might have found Samuel’s suggestion as unnerving or disgusting, especially given how those bodies were acquired, the emotional space of surgery allowed for such exchanges of macabre and candid humour.

I thoroughly recommend a visit to Leeds University Special Collections if you have the opportunity. There is also a publicly accessible display, Treasures of the Brotherton Gallery, which showcases some of the wonderful collections in the archives. I also recommend a visit to the Hey archive on the Leeds Special Collections website. I'm looking forward to finding out more about Samuel's training and hopefully sharing more of his work in my research.

[1] The Hey family tree contains several notable surgeons, including William Hey I (1736 – 1819) and William Hey II (1772–1844). Due to eponymous naming in this somewhat confusing family tree, Samuel Hey’s brother is also called William Hey, and will be referred to here as William Hey III; William Hey III was not a surgeon but a Clergyman. Please refer to the Leeds University Special Collections information pages for more information on the Hey family.

[2] Leeds Special Collections, MS 1991/3/8, 26th August 1831

[3] Leeds Special Collections, MS 1991/3/9, 15th September 1831; The letter has some damage after ‘afraid of the dying’ where part of the paper is torn, the quote continues from the next complete sentence.

[4] Leeds Special Collections, MS 1991/3/13, 8th February 1832

[5] Leeds Special Collections, MS 1991/3/13, 8th February 1832