It’s almost a cliché to acknowledge that humour is used in difficult situations to defuse tensions or to alter the mood.

But in these last few months, we’ve seen a proliferation of jokes regarding the Covid-19 crisis: most frequently, through memes and tweets, such as the many humorous takes on the government’s official coronavirus advice and graphics.

I’ve found this interesting in the context of my research on the visual culture and humour of plastic surgery during the Second World War. Humour, in both images and words, thrived in the plastics wards. But here I’d like to focus on two particular surgical technologies that were used to treat patients with facial injuries and burns: the skin flap and the tube pedicle.

A skin flap is exactly what it sounds like: a surgically detached flap of skin that can be transferred to another area. For a tube pedicle, the skin is rolled to prevent infection, and both ends of the tube are attached to the body to ensure blood flow before one end is removed and connected to the injury so that it can be sculpted into a new nose or chin. Thousands of drawings and photographs were made during the Second World War of these surgical techniques. But there were also images of and comments on these tubes and flaps that play on their strangeness through humour.

Tube pedicles became a ubiquitous tool for facial reconstruction during the First World War. Harold Gillies remarked on them often in his 1957 book The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery. As the most prominent plastic surgeon in Britain in the twentieth century, Gillies’s sense of humour contributed significantly to the culture of the field. In his typically humorous and exaggerated manner, Gillies wrote that his World War I plastic surgery ward in Sidcup ‘soon resembled the jungles of Burma, teeming with dangling pedicles.’[1] This incongruous description jars with our understanding of the tube pedicle as an invasive, uncomfortable object for the patient to whom it is attached. Gillies commented on the tube pedicle again about a hundred pages later in the book:

If all the tube pedicles that I have made and those my assistants have made were laid end to end, by calculations at two and a half pedicles per week, they would string like sausages from Buckingham Palace down the Mall, straight on through the Admiralty Arch to Trafalgar Square and half-way up Nelson’s monument. It is my ambition that before my last pedicle is made we will reach the top of this famous pinnacle with at least one pedicle left to go into the Admiral’s palate.[2]

Gillies’s ability to make jokes like this suggests either that he could detach himself—physically, emotionally, or temporally—from the suffering inflicted by this surgical technique, or that the humour is itself a manifestation of Gillies’s own trauma. There is also the possibility that Gillies, and other surgeons, could have utilised humour as a coercive, perhaps patronising, tactic: one that could make their patients feel like their traumas were minimal or less serious. Whatever the justification for this tone, Gillies successfully infuses the tube pedicle with humour through his animated language.

Perhaps surprisingly, facial surgery patients themselves made similar comments about their tube pedicles. Some patients gave this unsightly and uncomfortable fleshly apparatus a humorous nickname: ‘dangle ‘um.’ There was a social group in Scotland, similar to one in England (the Guinea Pig Club), that was formed around this particular trial of facial reconstruction, called The Dangle ‘Ums Club.[3] This language trivialises and infantilises the tube pedicle—such a light-hearted name lessens the fear of and aversion to the surgically constructed roll of flesh.

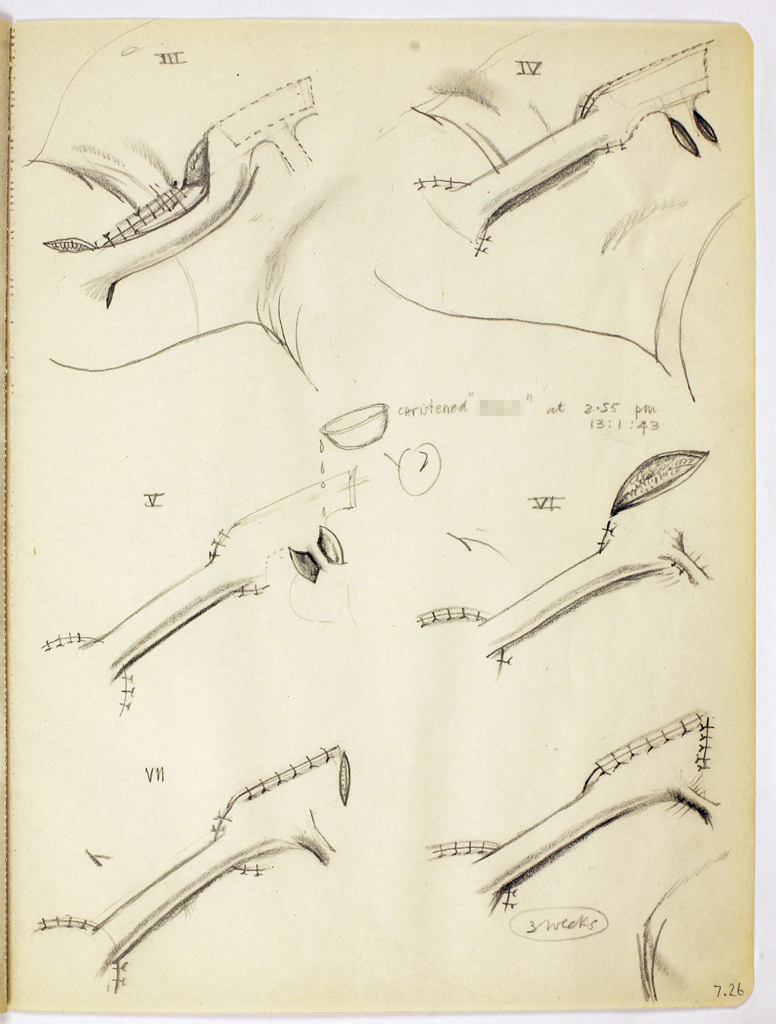

A similar goal is met in a drawing by the artist Dickie Orpen, who was based in St Albans at Hill End Hospital’s plastic surgery ward during the Second World War. In this image, a combination skin flap and tube pedicle is being transposed. Even though this is a highly specialised image, meant to show the numbered steps of this surgical procedure, it is also transgressive in its sense of humour. In the centre of the image, the surgical artist has ‘christened’ the roll of flesh with the name ‘Angus,’ dating it January 13th, 1943, 2:55 pm. There is room in this page, and in the surgical ward as a whole, for play and humour in the face of pain and distress.

Like Orpen, Gillies used images to imbue tube pedicles and skin flaps with humour. Gillies’s 1957 book is incredibly odd; not only is it written in a humorous tone (evident in the tube pedicle quotations above), but the descriptions of some truly horrific facial injuries and full-body burns are often accompanied by irreverent cartoons and photographs. One reviewer called it ‘a combination of autobiography, an unorthodox text, an informal reference book, filled with the most astounding array of illustrations ... as well as a complete drama in the development of plastic surgery.’[4]

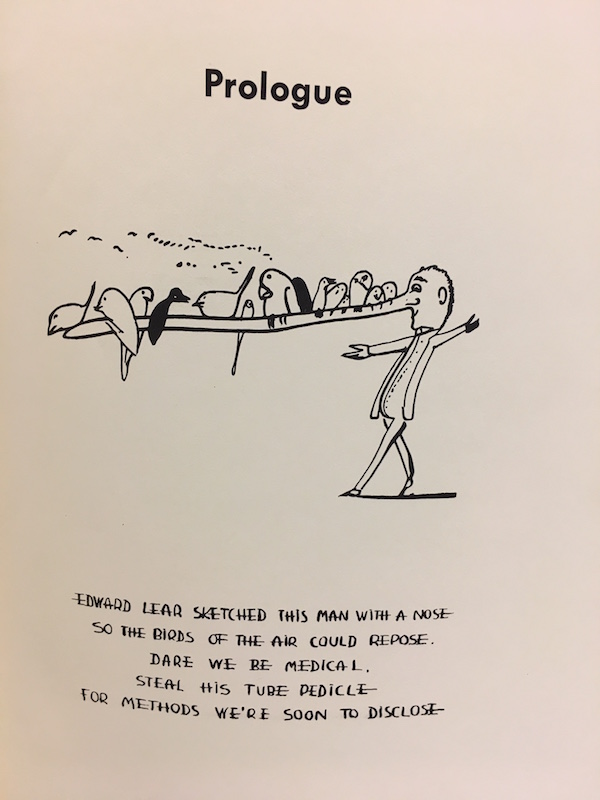

In the prologue, there is an image of a man with a long nose with birds perched upon it, drawn by the artist and nonsense poet Edward Lear (who happened to be Gillies’s great-uncle). The poem below it humorously states that this nose could be stolen and used as a tube pedicle. But perhaps the strangest image in this book is in the section on ‘Direct Flaps,’ on a page describing ‘The “Marsupial” Flap.’ Here, Gillies inserted a photograph of a surgeon into the ‘pouch’ that the flap makes around a real patient’s abdomen. In my research on this topic and this period, it seems that there are few lines that humour cannot cross in plastic surgery, as even an ostensibly serious publication by two established surgeons can have a visual joke like this within it.

![Gillies, Harold, and D. Ralph Millard, Jr. The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery, vol. 1, p. 151, 1957, published by Butterworth & Co. [full page and detail as featured image]](http://www.surgeryandemotion.com/content/images/Gillies_1957_Marsupial_Flap_2.JPG)

As I’ve alluded to above, the question of who is making these visual and verbal jokes matters. There are ethical and personal differences between patients making fun of their own faces, surgical artists adding humour to the depicted procedures, and surgeons making light of their practice. Further thought and research will have to be given to these questions of coercion, agency, and humour in a longer piece of writing, but this blog post hopefully begins the conversation.

[1] Harold Gillies and D. Ralph Millard, Jr. The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery (London: Butterworth & Co., 1957), 1: 37.

[2] Gillies and Millard, The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery, 1: 153.

[3] Brenda McBryde, A Nurse’s War (London: Hogarth Press, 1979), 60.

[4] Albert D. Davis, ‘The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery,’ California Medicine 87, no. 1 (July 1957): 67.

Christine Slobogin is a final-year PhD candidate at Birkbeck, University of London. Her thesis research—which lies at the disciplinary intersection of art history and the medical humanities—focuses on World War II surgical drawings by Dickie Orpen and their interactions with feminist art history, trauma, the archive, emotion, and humour. After finishing her thesis, she will be funded by the Wellcome Trust ISSF to continue her research at Birkbeck. She is also Sales & PR Manager at Eames Fine Art, the Newsletter Editor for the CAA-affiliated society Historians of British Art, and author of the blog Morbid Art History.